Undecidability Does Not Kill Simulation

Why “Consequences of Undecidability in Physics on the Theory of Everything” confuses provability with execution and replaces physics with a truth oracle.

Forward

Updated January 6, 2026

This article was expanded after repeated replies to the original post continued to miss the same central point. No new objections were being introduced. Instead, the same objection was being restated in progressively more technical language, while the underlying conceptual error remained unchanged.

Across subsequent exchanges, the anti-simulation claim was reframed using black hole physics, quantum measurement theory, Tsirelson bounds, entanglement structure, vacuum fluctuations, and related topics. Although the vocabulary shifted, the logical move did not. In every case, limits on prediction, certification, or global classification were being mistaken for limits on dynamical generation. Undecidability, randomness, inaccessibility, and failure of local hidden variable models were repeatedly treated as if they implied failure of algorithmic execution, even though those are distinct notions with well-defined meanings.

The expanded discussion section isolates this confusion and explains why it persists. It shows why undecidability constrains what can be decided or proven about a process, not whether the process can exist or run. It also explains why insisting on precise definitions strips away metaphor and forces the debate down to a single, concrete question. That question is whether limits on decision procedures imply limits on execution. Once stated plainly, the answer follows directly from standard computability theory, and the anti-simulation argument no longer converges.

Original start of the article:

A recent paper by Mir Faizal, Lawrence M. Krauss, Arshid Shabir, and Francesco Marino argues that undecidability and incompleteness place structural limits on any algorithmic Theory of Everything and, by extension, imply that the universe cannot be a simulation. The paper leans on Gödel, Tarski, and Chaitin, and it presents its conclusion as a consequence of mathematical physics rather than speculation. That framing is powerful, and it is also precisely where the argument breaks.

My goal in this response is not to “prove we live in a simulation,” and it is not to dismiss undecidability in physics. Undecidability results in quantum many body theory are real, and they are among the most fascinating bridges between computation and fundamental physics. My goal is narrower and more decisive: I want to show that the paper’s anti simulation conclusion does not follow from the theorems it cites, because it repeatedly conflates limits on formal derivability with limits on physical generation.

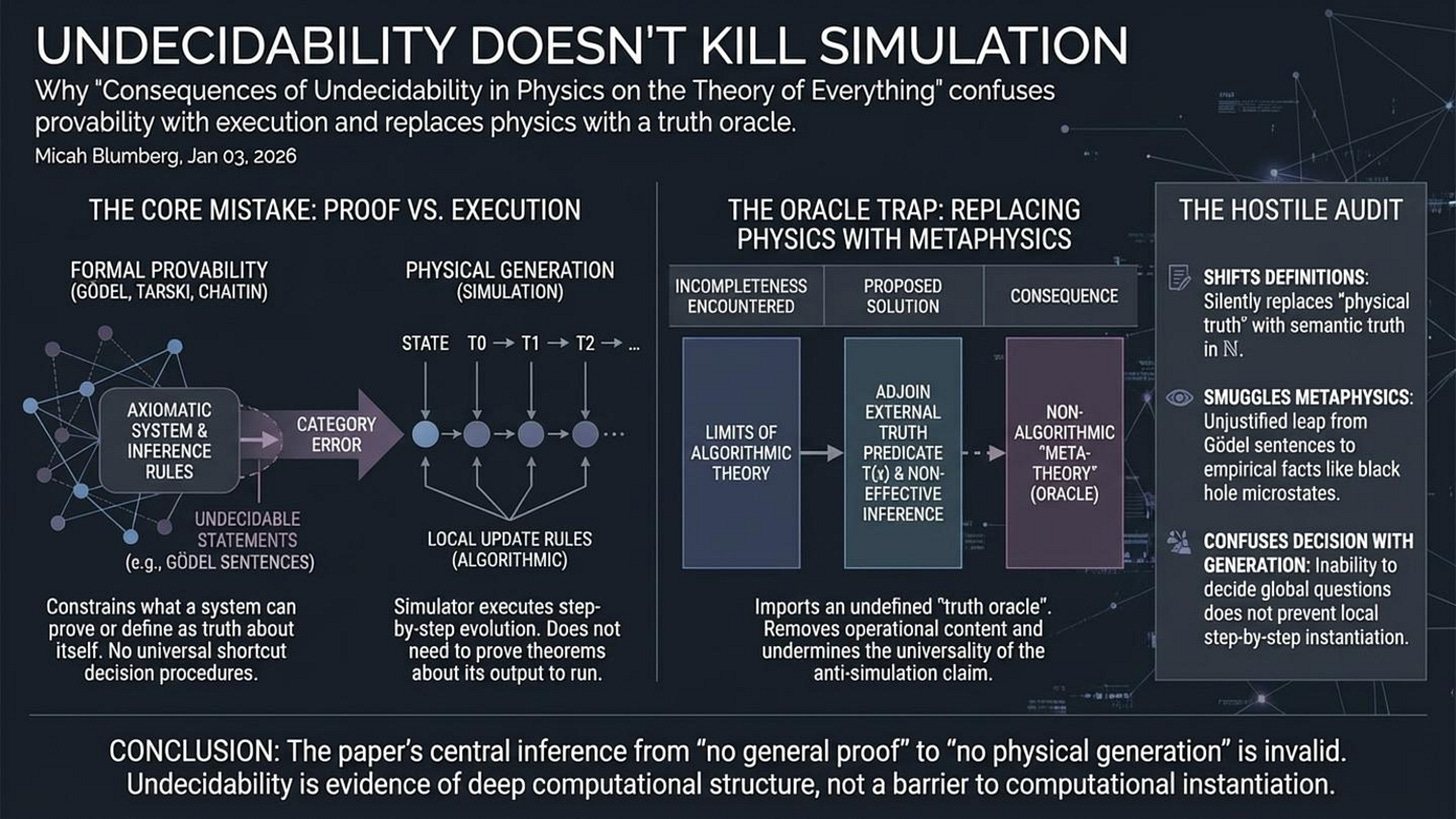

The core mistake is simple. A proof theoretic limit is not a dynamical limit. Gödel and Tarski constrain what a formal system can prove about itself or define as “truth” within its own language, but a simulator does not need to prove theorems about its output in order to run the process that generates that output. Likewise, undecidability blocks universal shortcut decision procedures for certain global questions, but it does not block step by step evolution under local rules. When you keep that distinction clean, the paper’s central inference chain collapses.

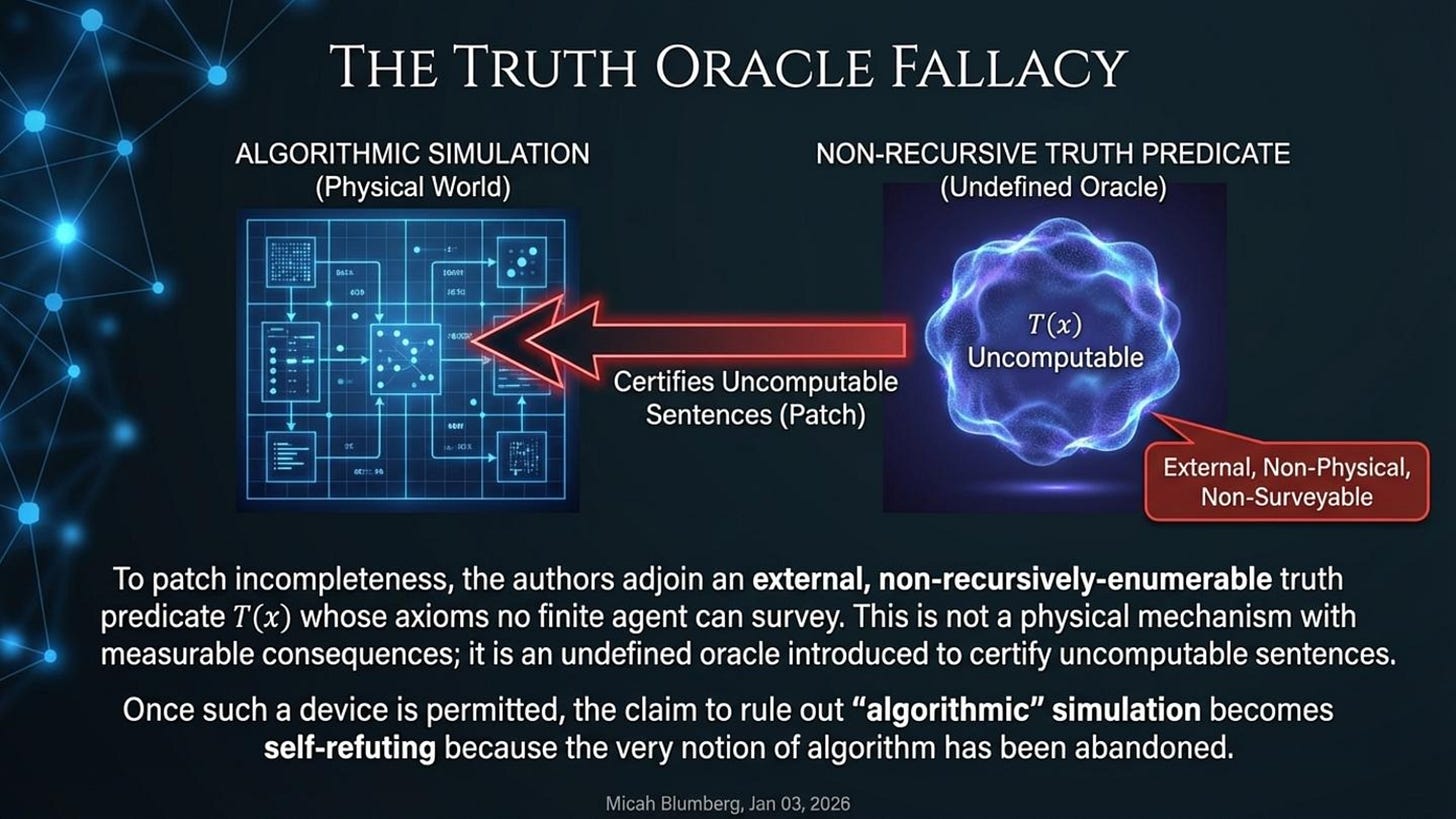

There is a second problem that matters just as much for scientific credibility. When the paper encounters incompleteness, it proposes an external truth predicate that “certifies” the uncomputable truths it wants. That move is not physics, because it replaces operational content with an oracle. It also undermines the universality of the paper’s conclusion, because once you allow external non effective truth resources, you have already stepped outside the very notion of “purely algorithmic” that the paper is trying to refute.

What follows is a hostile but fair audit of the logic. I will show exactly where the paper shifts definitions, where it smuggles metaphysics into mathematics, and where it confuses the inability to decide certain statements with the inability to generate the world those statements are about. The result is not that undecidability becomes irrelevant, but that it points in the opposite direction: it is evidence of deep computational structure in physics, not evidence that physics cannot be computationally instantiated.

This paper is trying to pull off a very strong conclusion using the wrong kind of machinery. It starts by framing quantum gravity as an axiomatic formal system and then argues that Gödel, Tarski, and Chaitin block any purely algorithmic Theory of Everything, and therefore block any simulated universe. That sounds crisp in the abstract, but the central inference chain fails once you separate three things that the paper repeatedly conflates: formal provability inside a theory, semantic truth in a chosen mathematical structure, and physical instantiation or evolution.

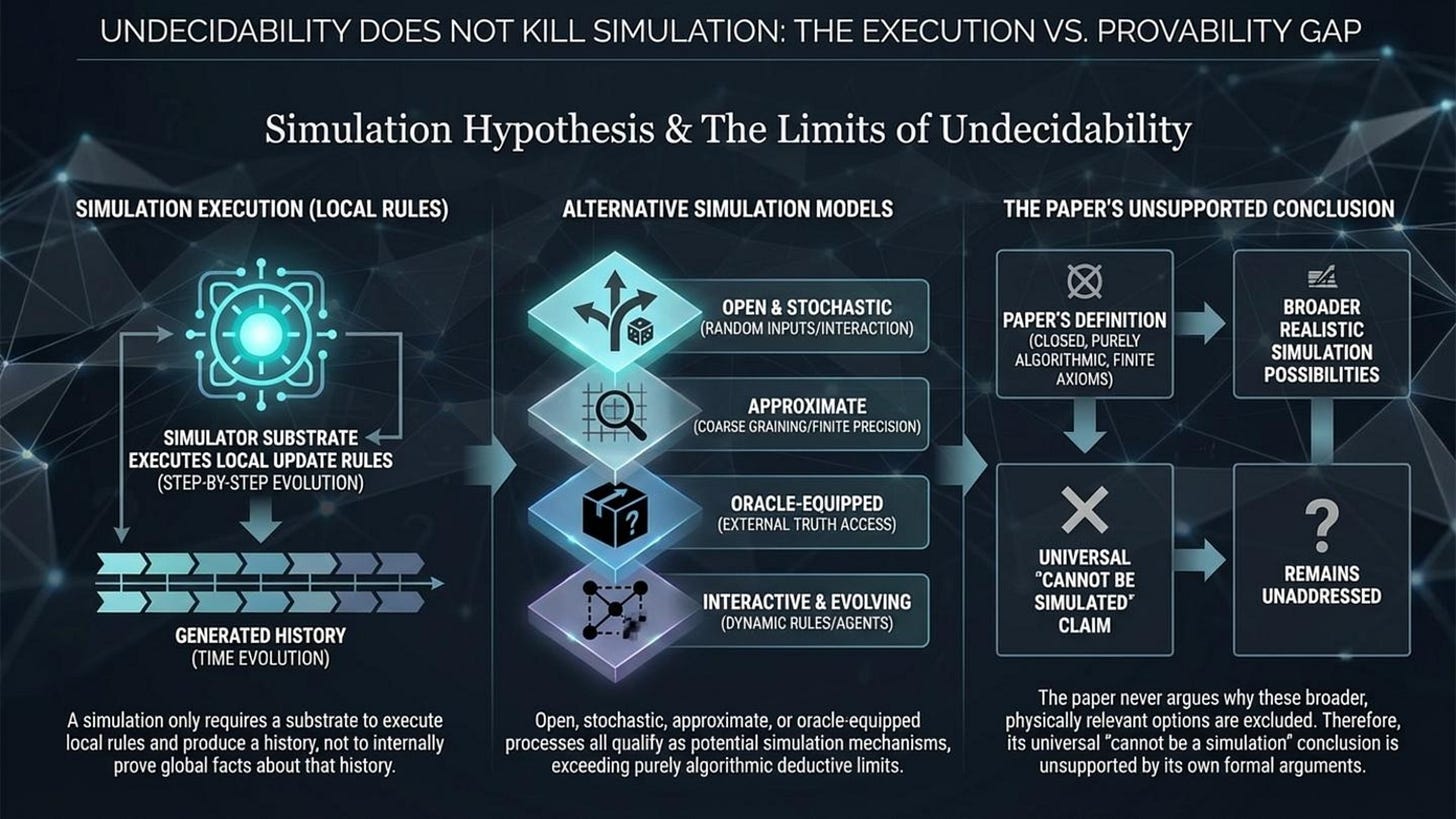

The biggest failure is the category error between “a formal system cannot decide or prove every truth expressible in its language” and “a physical universe cannot be generated by an algorithm.” A simulation does not need to prove theorems about itself, and it does not need a complete axiomatization that decides every global question about the simulated dynamics. A simulator can simply execute local update rules and generate a history. Gödel style incompleteness is about what follows from axioms under inference rules, not about whether a process can run. The fact that there is no algorithm that decides some global property of an entire class of systems does not prevent an algorithm from instantiating one particular system in that class and evolving it step by step. You can fail to decide a property and still generate the object whose property you cannot decide.

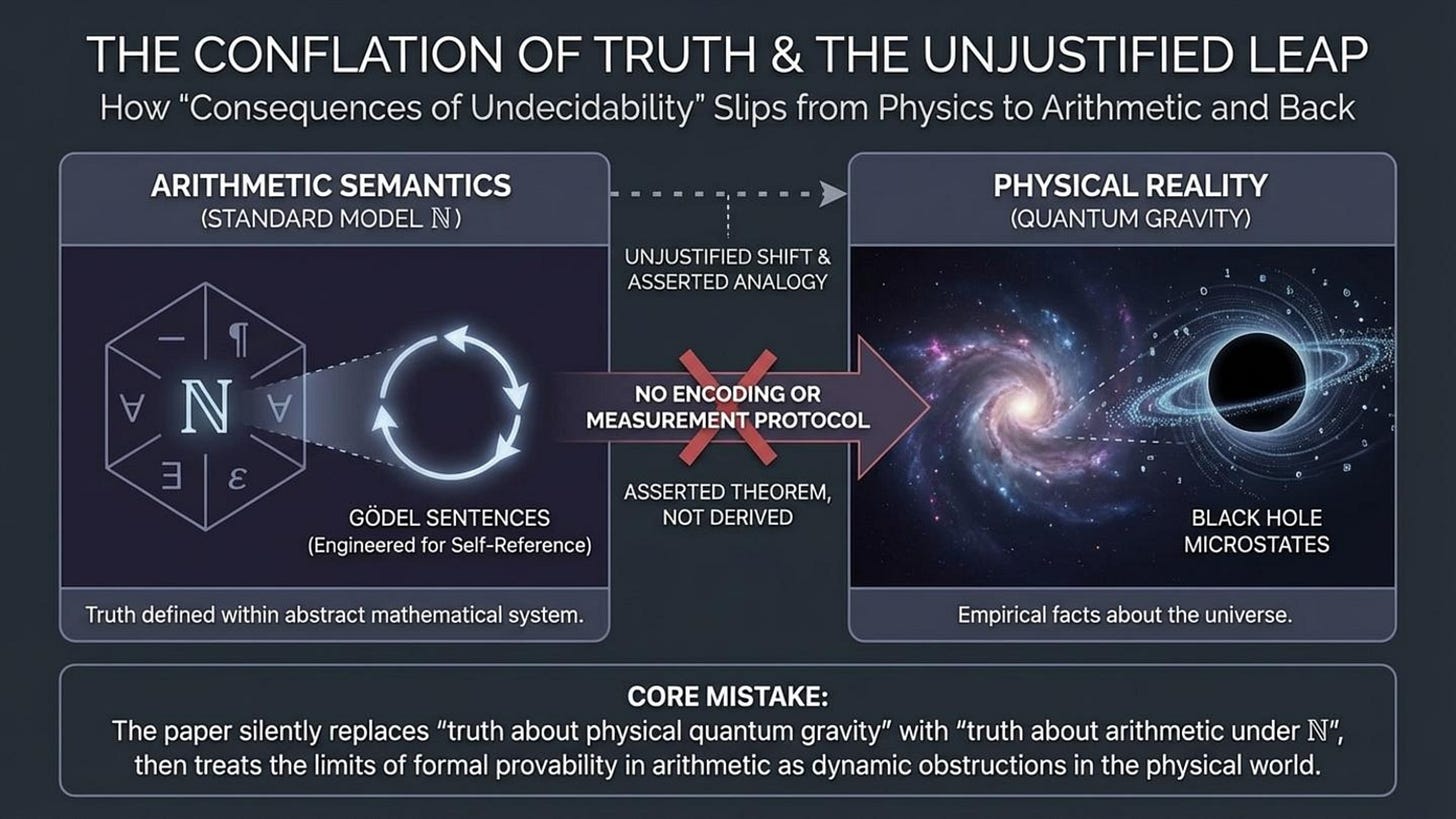

The paper then doubles down by building a formal object FQG and defining the “true sentences” of quantum gravity as those true in the standard natural numbers. That is an extraordinary move, because it silently replaces “truth about quantum gravity” with “truth about arithmetic under a specific intended model.” The moment you define semantic truth using ℕ as the model, you have stopped talking about the physical world and started talking about a mathematical structure that you selected. That choice is not justified, and it is not physically motivated. Even as mathematics, it undermines the physics claim because it relocates “reality” into arithmetic semantics and then treats incompleteness as a physical obstruction.

The most visibly weak sentence in the paper is the claim that the Gödel sentences of this formal system correspond to “empirically meaningful facts” like “specific black hole microstates.” This is a rhetorical leap, not a derivation. Gödel sentences are engineered self referential arithmetic statements whose truth is guaranteed relative to consistency and expressiveness assumptions. A black hole microstate is a physical configuration in a proposed theory. You do not get from one to the other without an explicit encoding, an explicit measurement protocol, and an explicit argument that the resulting statement has the self referential structure required for Gödel’s theorem to bite in the way you claim. The paper provides none of that, and without it, the microstate claim reads like an analogy that is being presented as a theorem.

There is a second, quieter technical fragility in the setup. The paper asserts a requirement that the axiom set be finite, and it ties that to the expectation that spacetime can be algorithmically generated. That is not a neutral assumption. It is a convenient assumption that makes Gödel and recursive enumerability arguments easy to narrate, but it also bakes in a particular philosophy of what a fundamental theory must look like. Even if you grant it, it still does not deliver the conclusion the authors want, because simulation does not require that the simulator possess a finite axiom list that proves all truths about the simulated world. It requires only that some process exists that generates the world’s state evolution, potentially with randomness, approximation, coarse graining, open system interaction, or external inputs.

The proposed “solution” called a Meta Theory is where the paper becomes operationally empty. It says, in effect, “we fix the incompleteness of the algorithmic theory by adjoining an external truth predicate T and a non effective inference mechanism, with a non recursively enumerable axiom set about T.” That is just importing an oracle. It is not a physical mechanism. It is not a model with measurable consequences. It is not even clear what it would mean for an empirical science to “use” a non recursively enumerable axiom set, because no finite agent can algorithmically access it. If the response to incompleteness is “assume a semantic truth predicate that certifies the uncomputable truths,” then the proposal is not explaining physics. It is redefining explanation to include an unreachable truth oracle and then declaring victory.

This also torpedoes the paper’s anti simulation conclusion from the other direction. If you allow yourself to postulate an external truth predicate that is not recursively enumerable, you have already left the ordinary notion of “algorithmic” behind. At that point, the paper is no longer refuting simulation in general. It is refuting only a narrow version where the simulator must be a closed, purely algorithmic, self contained deductive engine that decides every truth. That is not what most simulation hypotheses require, and it is not what most computational models in physics require either. A simulator could be open, interactive, stochastic, approximate, or equipped with an oracle. The paper never justifies why those possibilities are excluded, and so it never earns the universal “cannot be a simulation” claim.

The paper then leans on Lucas Penrose and objective collapse style ideas to argue that human cognition has access to Gödelian truth in a way computers cannot, and that quantum gravity supplies the truth predicate that collapse exploits. As a hostile referee, the correct response is that this is speculative philosophy layered on speculative physics, and it does not close the logical loop the authors need. Even if you granted every controversial premise, it still would not establish that physical reality is non algorithmic in the sense relevant to simulation. It would establish, at most, that some forms of prediction, proof, or compression are limited for agents inside the system.

The end result is that the paper’s central claim is not supported by its own formalism. It smuggles in the conclusion through shifting definitions of “truth,” through unjustified identifications of Gödel sentences with physical facts, and through a deus ex machina truth predicate that replaces computation with an oracle and then declares that computation failed. If this were submitted as physics, it would be rejected for lack of operational content. If it were submitted as logic applied to physics, it would be rejected for conflating semantic truth in ℕ with truth about the world, and for making universal metaphysical conclusions from the limits of formal provability.

If you want the strongest one sentence hostile verdict, it is this. The paper mistakes limits on formal derivability and global decision procedures for limits on dynamical generation, and then it papered over the gap by postulating an undefined truth oracle while still claiming an empirical refutation of simulation.

In conclusion the paper’s headline fails for one structural reason. It confuses limits on provability and decision procedures with limits on dynamical generation. Undecidability and incompleteness are constraints on what can be decided, proven, or compressed from within a formal description, but they are not constraints on what a rule based process can instantiate by stepwise evolution.

The argument equivocates on “simulation” by treating it as a complete algorithm that can decide all truths about the simulated universe, even though a simulation only needs to execute local update rules and generate a history. Gödel and Tarski are misapplied because they restrict what can be proven or what “truth” can be defined inside a formal system, not what an algorithm can run, and a simulator does not need to prove or internally define all truths about its own output. Chaitin is misused because incompressibility or unpredictability for an observer does not imply noncomputability of the generator, and the paper does not identify any physically measurable quantity that is provably noncomputable. The paper then makes an unjustified leap by defining “true sentences” as those true in ℕ and treating that semantic notion as physical truth, while never justifying the step from Gödel sentences to concrete empirical facts like black hole microstates. Finally, the paper’s escape hatch is an external truth predicate and a non recursively enumerable axiom set, which is simply an oracle, and that move removes operational scientific content while also undermining any claim to have ruled out simulation in general.

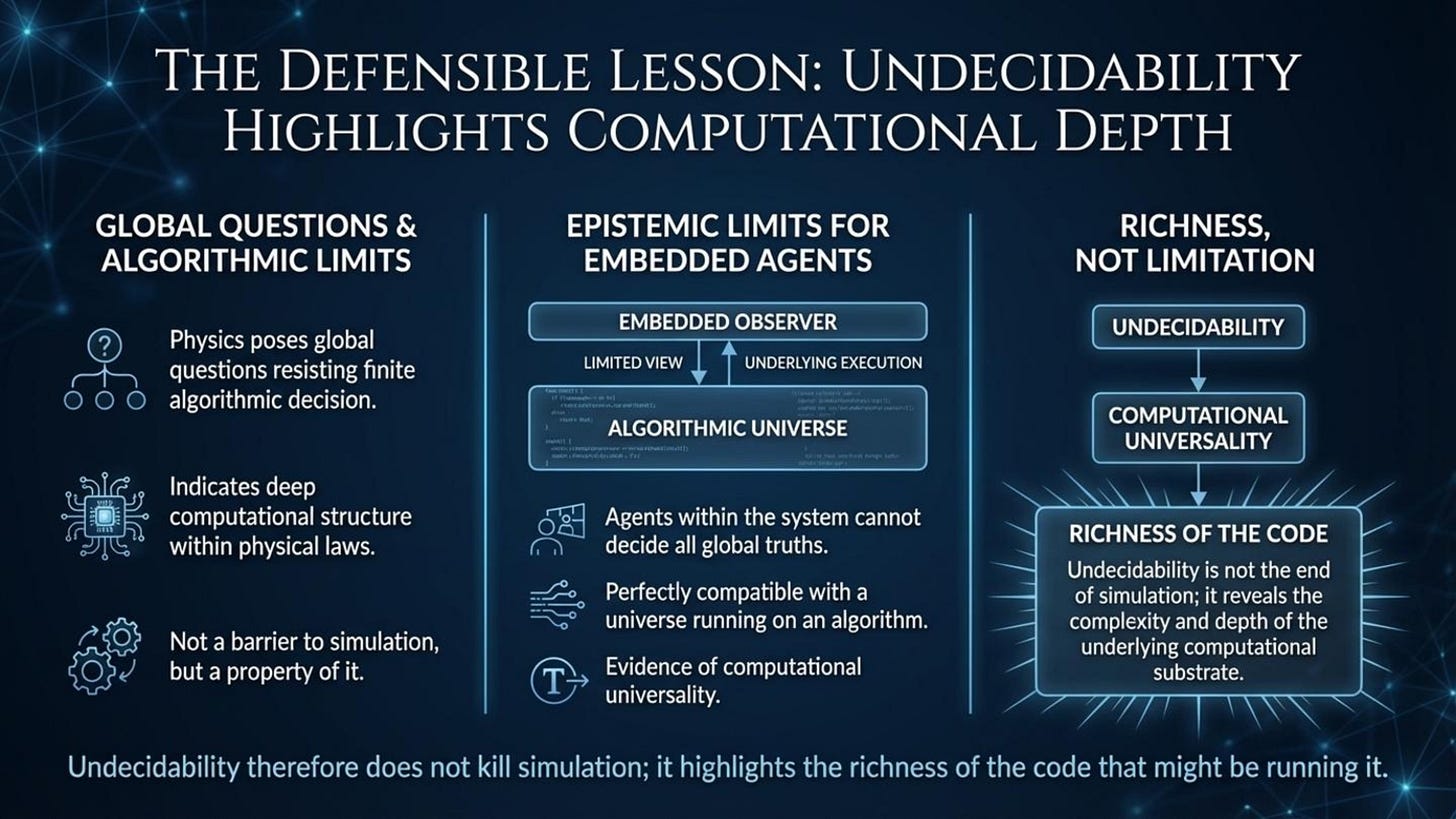

If the authors had stopped where the mathematics genuinely stops, their conclusion could have been valuable. The defensible claim is that there are hard limits on universal prediction, classification, and compression from finite descriptions, and that physics can contain well posed global questions whose answers no general algorithm can decide. That is a deep and important point about epistemic limits for agents inside the universe. It is not, and never becomes, a proof that the universe cannot be generated by an algorithmic substrate. In fact, the existence of undecidable physical decision problems is perfectly compatible with an algorithmic world, and it is often evidence of computational universality rather than evidence against computation.

Discussion: Why the Confusion Persists

After publishing this rebuttal, several physicists and philosophers responded by reformulating the same objection in different language. The terminology varied. Some emphasized “ontological sufficiency.” Others appealed to black holes, inaccessible microhistories, or irreducible physical processes. Despite the surface differences, these responses all share the same underlying structure, and they all fail for the same reason.

The common move is to concede that physical processes may generate outcomes, while simultaneously claiming that because the internal path is undecidable, inaccessible, or unreconstructible, computation is therefore ontologically insufficient. This is simply the original error restated in physical language. It replaces logical undecidability with epistemic inaccessibility and then treats that replacement as an ontological failure.

One response framed the issue in terms of black holes and trans-Planckian physics, suggesting that outcomes may be generated but that how they are arrived at cannot be determined, and that this gap undermines computational generation. This actually reinforces the argument made here. Something can be generated even if no observer can reconstruct the internal steps that produced it. Loss of predictability or retrodictive access does not negate generation. It only limits what agents inside the system can know. Undecidability theorems formalize exactly this distinction. They place limits on decision and reconstruction, not on existence or evolution.

Another response insisted that a computational substrate must be “ontologically sufficient,” and that undecidability shows no closed algorithm can meet that standard without invoking an oracle. But this conclusion only follows because “ontological sufficiency” has been quietly redefined to mean “internal decidability of all physically meaningful truths.” That requirement is not imposed on physical reality itself. The universe does not decide or certify its own global properties before evolving. It instantiates states. If ontological sufficiency is defined to require omniscient internal decision power, then the argument becomes true by definition and vacuous as a claim about physics.

In every case, the same confusion reappears. Undecidability is repeatedly mistaken for a limit on existence, when it is actually a limit on universal prediction, compression, and formal proof. But undecidable does not mean ungenerated. A process can instantiate facts that no algorithm can universally classify. A generative process can produce histories whose long-term or global properties admit no universal decision procedure. This is not a flaw in computation. It is a defining feature of computational universality.

Once the run versus decide distinction is kept explicit, the anti-simulation argument loses its footing. Oracles are needed for decision procedures, not for evolution. Inaccessibility is not an oracle. Randomness is not hypercomputation. And the inability of observers to determine how an outcome was arrived at does not imply that the outcome was not generated by local rules.

This is why the argument fails, and why it continues to fail even when recast in the language of black holes, quantum measurement, or ontological sufficiency. The problem is not the physics. The problem is the category error.

The argument in “Consequences of Undecidability in Physics on the Theory of Everything” has already collapsed under close inspection, even though its proponents do not yet see it. They believe they are making a deep structural claim, but they have missed a basic distinction, and once that distinction is made explicit their conclusion collapses.

The mistake is that a philosophical requirement was quietly imported into the notion of computation without being examined. Once that requirement is assumed, everything that follows feels inevitable, so the argument is never walked back step by step to check whether the premise itself is justified. It is not.

The confusion is sustained by keeping the discussion at too high a level of abstraction. Words like “ontologically sufficient,” “oracle,” “truth,” and “algorithmic” are doing hidden work, and instead of clarifying the issue they obscure it.

The fix is to force a concrete distinction that cannot be slid past. That distinction is between physical evolution itself and the ability to certify, decide, or globally characterize what that evolution will do. Undecidability restricts universal classification and prediction of global behavior. It does not prevent a process from unfolding through its local dynamics. A Turing machine can execute a program whose halting behavior is undecidable. The program still runs. Physics does not need to decide its own future in order to exist. It just evolves.

That is the entire point, and it is the point they cannot refute.

Another way to see this is through Conway’s Game of Life. There are undecidable questions about its global behavior. Does that mean Life cannot be generated by rules? Of course not. It means you cannot shortcut its behavior. Physics being like Life is an argument for computation, not an argument against it.

To be clear, I am not claiming that a simulator can certify all truths about the universe. I am claiming that a substrate can generate the universe. Undecidability is irrelevant to generation.

Something can be generated even if the path by which it is generated is not reconstructible or decidable by an observer. Hawking radiation being measurable while its microhistory is inaccessible does not imply a non-computational origin. It implies loss of predictability and loss of retrodictive access. Those are epistemic limits, not limits on generation. A process does not stop being algorithmic simply because no observer can recover or decide its internal steps. That distinction between generation and decidability is exactly what undecidability theorems formalize, and it is where the anti-simulation argument keeps going wrong.

Several responses now argue that physics produces outcomes that are “not computable,” citing quantum measurement, Tsirelson bounds, or information hidden behind horizons as evidence. This framing still confuses three distinct notions: generation, inference, and explanation.

Constraints like Tsirelson bounds limit observable correlations and prevent superluminal signaling. They do not transform an executed physical process into a noncomputable oracle. They restrict what can be inferred from outputs, not what can be generated by underlying dynamics. Information being inaccessible or unreconstructible to observers is an epistemic limitation, not a proof that the generating process is nonalgorithmic.

Likewise, claims that quantum measurement outcomes are “not computable” typically collapse into one of two weaker statements. Either they mean that no deterministic classical program can reproduce the exact same outcome sequence without randomness, which is trivial and already acknowledged by quantum theory, or they mean that exact, efficient classical simulation of arbitrary quantum systems is infeasible, which is a statement about computational complexity, not computability. Neither establishes the existence of a physically measurable quantity that is provably non-Turing-computable.

The repeated claim that a Turing machine “cannot emulate how quantum outcomes happen” again shifts the target. Emulation means producing the correct operational statistics, not supplying the correct metaphysical narrative. This argument does not depend on any particular interpretation of quantum mechanics, but only on operational distinctions between execution, prediction, and decision in computation. A simulator does not need to explain why a particular outcome occurred. It only needs to generate outcomes with the correct distribution. Conflating explanation with execution is the same run-versus-decide error, translated from logic into physical language.

Finally, invoking black hole horizons, trans-Planckian regimes, or inaccessible microhistories does not rescue the argument. Something can be generated even if no observer can reconstruct the internal steps that produced it. Hawking radiation being measurable while its microhistory is concealed does not imply a noncomputational origin. It implies limits on retrodiction and inference. Those limits are exactly what undecidability and no-go theorems formalize. They do not imply that the underlying dynamics cannot be rule based.

At this point, the pattern is clear. Each reformulation replaces “undecidable” with “inaccessible,” “nonclassical,” or “unexplainable,” and then treats that replacement as an ontological failure of computation. But none of these moves escape the same mistake. Undecidability, randomness, and inaccessibility constrain prediction and explanation. They do not constrain generation.

Why the Discussion Keeps Looping

At this point, what is stopping the conversation from converging is not a lack of intelligence. It is that the objection keeps sliding between different claims, so the target changes midstream. The result is that one side believes it is refuting my point, while it is actually refuting a different point that it already knows how to argue about.

The first conflation is between incomputable and nonclassical. When some critics say “incomputable,” they are not using the term in the strict Turing sense. They are using it to mean that no local hidden variable model can reproduce quantum statistics, or that a classical deterministic model cannot reproduce quantum measurement outcomes, or that a classical computer cannot efficiently emulate generic quantum dynamics. Those are all real and well known statements. None of them, however, is a statement of incomputability in the technical sense. They are statements about nonlocality, contextuality, or computational complexity. As long as “incomputable” is used as a synonym for “not locally classical,” the run versus decide distinction will never land, because I am talking about decision versus execution while the reply is talking about Bell and hidden variables.

The second conflation is between oracle, randomness, and inaccessibility. Some replies keep calling quantum outcomes “oracle-like.” That is a metaphor unless it is made precise. In computability theory, an oracle is a device that decides an undecidable language, such as the halting set. Quantum measurement outcomes do not do that. Randomness is not an oracle. Inaccessibility behind horizons is not an oracle. A result being unpredictable or not reconstructible does not make it hypercomputational. The word oracle keeps being used because it feels like the right shape for mysterious output, but in computation theory it refers to a very specific kind of decision power that quantum measurements do not provide.

The third conflation is between “cannot compute a complete reproduction” and “cannot generate a history.” When a critic says local hidden variables cannot compute dynamics that reproduces quantum outcomes, what they are actually saying is that Bell type results rule out a certain class of local hidden variable completions. That has nothing to do with whether a computational substrate can generate the universe. A computational substrate could generate quantum statistics without being a local hidden variable theory, and without granting any extra decision power at all. The anti-simulation argument I am rebutting requires a much stronger claim, namely that physical reality contains provably non-Turing-computable observables accessible to finite agents. That claim is not being provided. A different no-go theorem is being substituted, and then the conclusion is being smuggled back in.

So this is not “people failing to understand.” It is people arguing inside a different conceptual box and repeatedly dragging the conversation back into that box because that is where their intuitions are anchored. They are treating nonlocality, inefficiency, unpredictability, and inaccessibility as if they were equivalent to incomputability and oracle decision power. They are not equivalent.

The only clean way to resolve this is to lock the definitions and force a single yes or no question.

The Oracle Question

At this point the disagreement is not about physics. The disagreement is about definitions.

In this debate, the word incomputable is often being used to mean “not reproducible by local hidden variables” or “not classically efficient to emulate.” In this article, I am using incomputable in the strict Turing sense, meaning “not computable by any algorithm.” Bell-type no-go results constrain local hidden variable completions. They do not, by themselves, establish the existence of non-Turing-computable observables.

Likewise, calling quantum outcomes “oracle-like” is only a metaphor unless it is made operational. In computability theory, an oracle is not a poetic label for something mysterious. An oracle is a device that provides decision power over an undecidable language, such as the halting set. So the discussion can be forced into a precise form by asking one concrete question.

Do quantum measurements provide decision power over an undecidable problem, yes or no.

If the answer is no, then quantum randomness is not an oracle in the computability sense, and undecidability does not imply that the universe cannot be generated by an algorithmic substrate. If the answer is yes, then the claim requires a concrete mapping from measurement outcomes to an undecidable language together with a physically realizable procedure that uses those outcomes to decide it with nonzero reliability. Without that mapping and procedure, the word oracle is doing no technical work and cannot support the anti-simulation conclusion.

Why the Oracle Question Makes Sense, and Why It Is Hard to Answer

The reason the key question sounds jarring is that most people are not used to the technical meaning of the word “oracle” in computability theory. In everyday speech, “oracle-like” just means mysterious, inaccessible, unpredictable, or beyond explanation. In computability theory, an oracle is not any of those things. An oracle is a very specific object. It is a black box that decides membership in a language that an ordinary Turing machine cannot decide, such as the halting set. The defining feature of an oracle is decision power over an undecidable problem.

That is why the following question is not rhetorical. It is the only way to prevent the discussion from drifting into metaphor.

Do you claim that quantum measurements provide decision power over an undecidable problem, yes or no.

This is where the conversation either becomes scientific and precise, or it remains rhetorical and impressionistic.

If the answer is no, then quantum measurement outcomes are not oracles in the computability sense. They may be random, inaccessible, contextual, or irreducible. None of those properties grant decision power over undecidable languages. In that case, undecidability places limits on prediction and proof, not on generation, and the anti-simulation conclusion collapses.

If the answer is yes, then the claim becomes extraordinarily strong, and it demands extraordinary specificity. A concrete mapping is required from measurement outcomes to an undecidable language, such as the halting problem, together with a physically realizable procedure that uses those outcomes to decide it. Without that mapping, the claim has no technical content. It is just the word “oracle” being used as a metaphor.

This is also why the question is hard for people to answer. It forces a retreat from comfortable, high-level language into a strict, operational claim. Many experts are trying to express a real intuition, namely that quantum outcomes are not locally classically explainable, and that there are principled limits on what observers can infer or retrodict. But those intuitions live in a different category than computability oracles. The moment you define “oracle” correctly, randomness and inaccessibility stop doing any logical work, because randomness is not decision power and inaccessibility is not computation.

The question feels hard because it exposes the gap between two different uses of the same words. In one use, “oracle-like” means “the mechanism is not reconstructible from within the system.” In the other use, “oracle” means “a device that decides an undecidable language.” The anti-simulation argument quietly slides between these meanings. My question blocks that slide.

Once this is understood, the debate becomes much simpler. Either quantum measurement provides genuine hypercomputational decision power, in which case a concrete halting-problem-style protocol must be produced, or it does not, in which case calling it an oracle is only metaphor and cannot support a claim that the universe cannot be generated by an algorithmic substrate.

Why Exotic Spacetimes and “Duck-Typed Oracles” Still Miss the Point

At this stage, the objection has shifted again, this time into a narrative involving Hogarth–Malament spacetimes, Zeno processes, Cauchy horizons, and information potentially encoded in Hawking radiation. While the physics vocabulary has become more exotic, the underlying mistake has not changed.

What is happening here is that the word “oracle” is being treated as an intuitive or phenomenological label rather than as a technical object with a precise definition. In computability theory, an oracle is not something that feels mysterious, inaccessible, information rich, or difficult to reconstruct. An oracle is defined by a single property: it provides decision power over a language that is undecidable for ordinary Turing machines, such as the halting set. Without that decision power, there is no oracle in the technical sense, regardless of how exotic the surrounding physics may appear.

The appeal to Hogarth–Malament spacetimes illustrates this perfectly. Even in the idealized setting, the claim is not that undecidable problems become decidable for finite agents in our universe. The claim is that certain observers might, in principle, receive arbitrarily long computations in finite proper time. That is a speculative model of hypercomputation under extreme idealization, not a demonstration of oracle access. Once realistic physics is reintroduced, including Hawking radiation, mass inflation, and Planck-scale cutoffs, even that speculative route collapses. At that point, the argument should end.

The move that follows, suggesting that the answers might nonetheless be “in” the Hawking radiation, does not rescue the claim. Information being present somewhere in the universe is not the same thing as an agent having decision power. To count as an oracle, one would need a physically realizable procedure by which a finite observer can extract correct yes-or-no answers to an undecidable problem with nonzero reliability. No such procedure is specified, because none is known. Information existing somewhere, even in principle, is not computation, and it is not decision.

What keeps the confusion alive is a continual slide between three different standards. One is an idealized “in principle” story under infinite or unphysical assumptions. Another is what is physically realizable under known laws. The third is an intuitive sense that something looks or feels like an oracle because it is inaccessible or hard to explain. Computability theory only licenses conclusions under the second standard. Sliding between these standards without fixing one is exactly how the conclusion keeps being smuggled in.

The “if it looks like a duck” analogy makes this explicit. In computability theory, appearances do not matter. Definitions do. An oracle is not defined by how mysterious it is, or by how difficult it is to reconstruct a process after the fact. It is defined by what it can decide. Exotic spacetime structure, inaccessible microhistories, or information hidden behind horizons do not automatically confer decision power over undecidable languages.

At this point, the disagreement is no longer substantive. It is a mismatch of questions. I am asking whether physics provides operational decision power over undecidable problems. The replies keep answering a different question, namely whether physics contains processes that are hard to reconstruct, inaccessible, nonclassical, or information rich. Those are interesting features of physical reality, but they are not what oracle means, and they do not imply that physical reality cannot be generated by an algorithmic substrate.

Once this distinction is kept explicit, the argument has nowhere left to go. Undecidability, inaccessibility, randomness, and exotic spacetime structure constrain prediction and explanation. They do not constrain generation.

A recurring confusion in anti-simulation arguments is the collapse of two logically distinct notions: executing a dynamical process and deciding global properties of that process from a finite description.

A simulation, in the minimal technical sense, is execution. It is the stepwise generation of a state history by local transition rules. Undecidability results constrain something different. They constrain universal decision procedures that, given a finite description of a system, would always correctly answer certain global questions about its asymptotic behavior, phase, or classification. These are limits on prediction, certification, and global classification, not limits on dynamical realization. A closed algorithmic process can generate histories whose global properties are undecidable to any internal or external agent, and this fact is standard in computability theory. Therefore, the existence of undecidable physical decision problems does not imply that a universe cannot be generated by algorithmic dynamics. It implies only that no agent can, in general, shortcut the computation by deciding all emergent truths in advance.

First, it is a category error to identify “the properties of the process” with “the dynamics” in the sense required by undecidability arguments.

Local dynamics specify what happens next, while undecidability concerns global semantic questions about the infinite or asymptotic structure of what those dynamics generate.

Second, it is a category error to infer non-simulability from unobservability. Physics and simulations both routinely involve hidden internal degrees of freedom, virtual intermediates, and quantities inferred only through effects. Indirect observability does not imply noncomputability.

Third, it is a category error to treat the absence of external validation as evidence against computation. A simulation does not require an external referee that certifies correctness at each step. It requires only a substrate that implements the update rules, which is precisely what “physical law” already means at the implementation level.

Finally undecidability is not an anti-computation result. It is a limit on universal shortcut methods for deciding truths about computations, including computations instantiated as physical systems, and it is therefore fully compatible with an algorithmic substrate for reality.

Conclusion

A scope clarification is essential. This rebuttal does not depend on adopting any particular version of the simulation hypothesis, nor does it privilege an external simulator, an embedded physical simulator, or a self-simulating universe as a matter of metaphysics. The argument targets a single logical leap that recurs across anti-simulation claims: the assumption that undecidable or unprovable global facts cannot be generated by an algorithmic process. That assumption is false. Undecidability constrains universal decision, certification, and prediction from finite descriptions. It does not constrain execution or dynamical instantiation. A process can run while many of its global properties remain undecidable to any internal or external agent. This distinction applies to any framework in which physical laws are realized through stepwise dynamics, regardless of where computation is located. What undecidability actually rules out is not simulation, but the inflated requirement that a simulator must be able to decide or certify all truths about what it generates.

Undecidability forbids a complete algorithmic description that can decide or certify all truths about reality from a finite specification. It does not forbid an algorithmic process from instantiating that reality through stepwise local evolution. A system can be fully generated while its global properties remain undecidable to any internal or external agent. This distinction is fundamental in computability theory and applies equally to physical systems and abstract computations. Once it is made explicit, claims that undecidable physics implies the impossibility of simulation no longer follow. Undecidability constrains prediction, classification, and proof. It does not constrain execution.

Replying to this letter:

Consequences of Undecidability in Physics on the Theory of Everything

AuthorsFrancesco Marino 4

https://jhap.du.ac.ir/article_488.html doi 10.22128/jhap.2025.1024.1118