Popular Mechanics Said This Gravity Theory Was New. It Wasn’t.

How a “groundbreaking” science story quietly erased prior work

When Popular Mechanics told readers that gravity might be evidence our universe is a simulation, it framed the idea as a startling new breakthrough.

The problem: the core claim had already been publicly published years earlier — before the cited paper was even submitted.

The dates are public. The articles are archived. And none of that prior work was mentioned.

What the Article Claimed — and Why It Matters

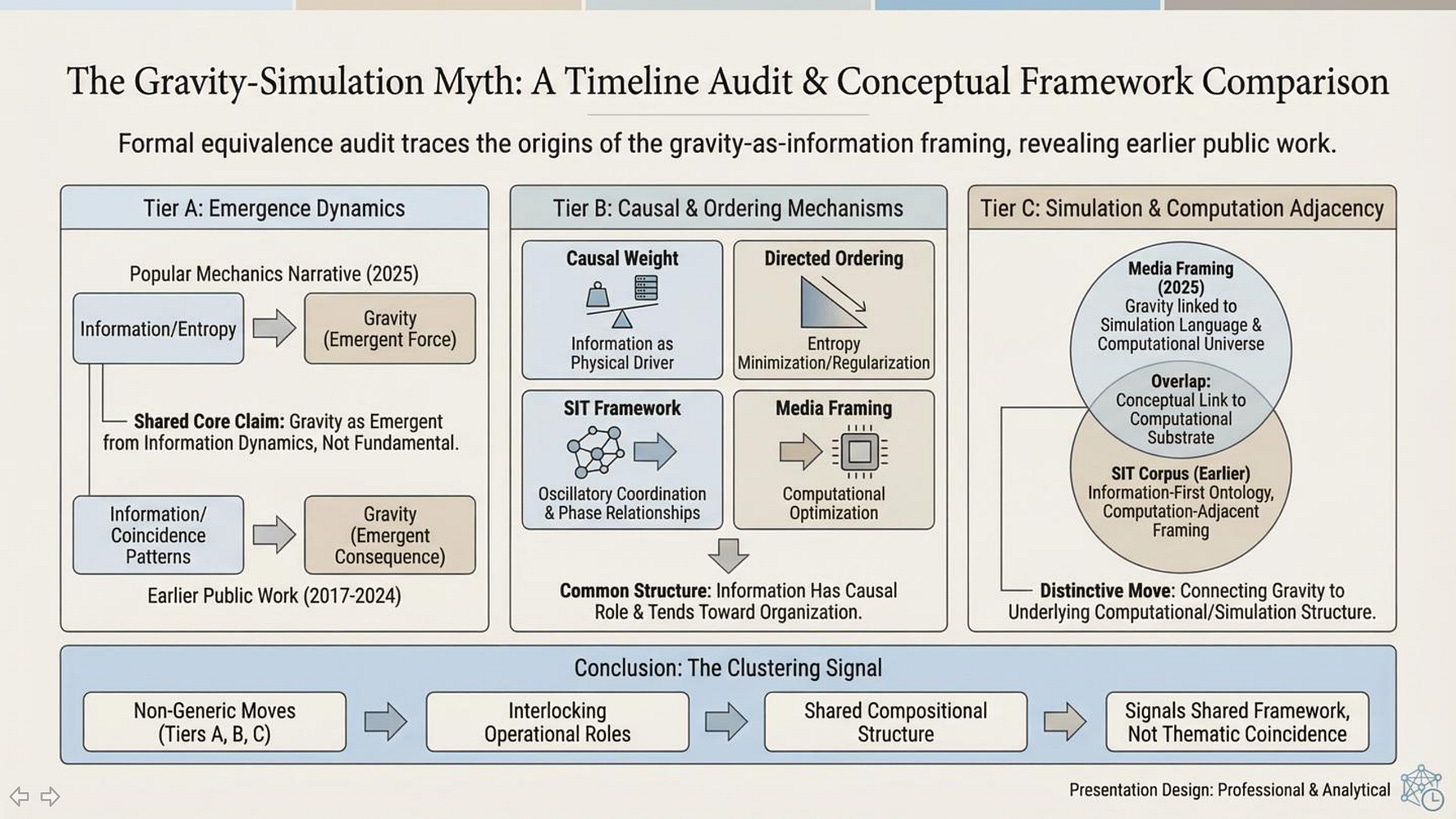

The Popular Mechanics article “Gravity May Be Key Evidence That Our Universe Is a Simulation, Groundbreaking New Research Suggests” presented the idea that gravity may function as an information-processing or optimization mechanism, with behavior that resembles computation rather than a traditional fundamental force. It further suggested that this informational framing could point toward a simulation-like structure of the universe, positioning gravity as part of an underlying computational substrate.

Crucially, the article framed this perspective as new and groundbreaking—the kind of conceptual shift readers are meant to understand as a fresh scientific development. That framing matters because it shapes how readers interpret the state of the field: what counts as a recent discovery, who is seen as advancing it, and how scientific progress is narrativized.

If the “newness” claim is inaccurate, then readers are not just missing background—they are being given a distorted picture of how and when the idea actually entered public scientific discourse.

The Missing Context: This Idea Was Publicly Published Earlier

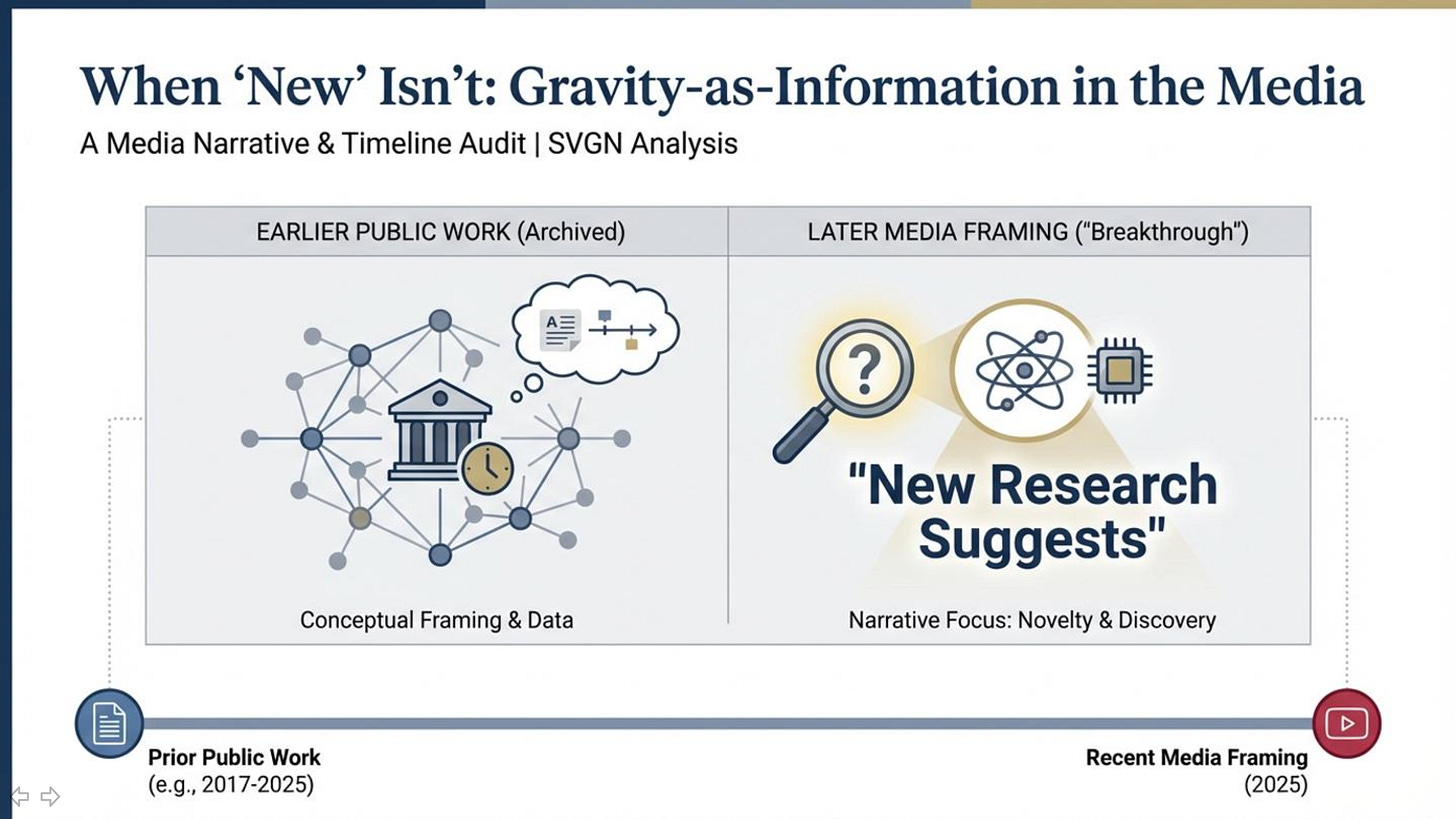

What the article did not mention is that this same gravity-as-information framing—treating gravity as an emergent consequence of informational organization, optimization, or compression rather than a purely fundamental force—had already been publicly developed and released years earlier in multiple stages across openly accessible publications.

This context was not mentioned, even though it directly affects the reader’s understanding of whether the claim is truly “new,” and whether the cited paper is best understood as an original breakthrough or as a later re-presentation of an existing conceptual move.

A Public, Verifiable Timeline

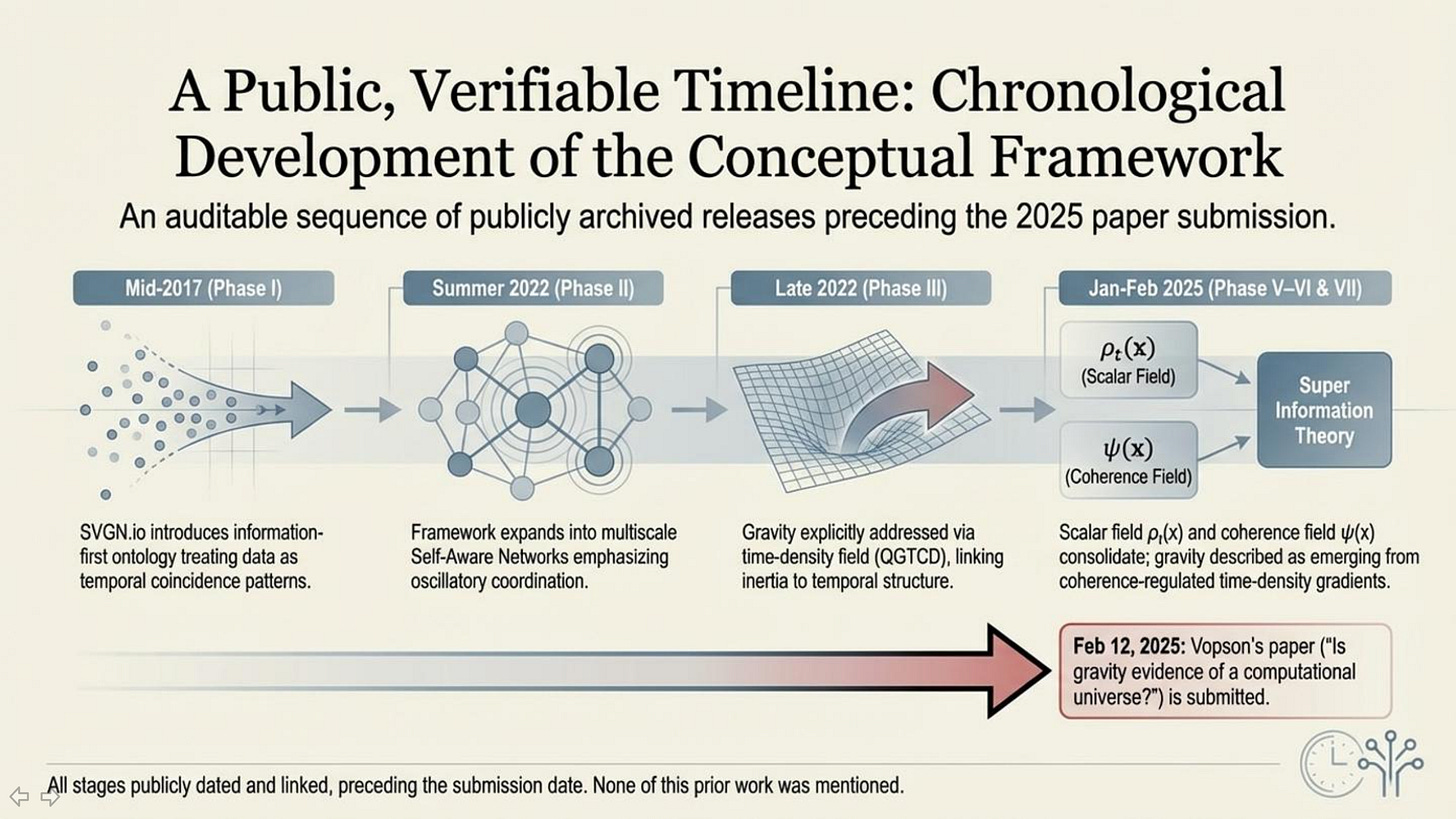

This is not a matter of interpretation. The publication timeline is public.

Below is a chronological list of the relevant releases and publication milestones, presented plainly so any reader can verify the sequence for themselves by checking the public links and timestamps.

Timeline (all publicly archived):

A Public, Verifiable Timeline

This is not a matter of interpretation. The publication timeline is public.

Below is a chronological list of the relevant releases and publication milestones, presented plainly so any reader can verify the sequence for themselves by checking the public links and timestamps.

Timeline (all publicly archived):

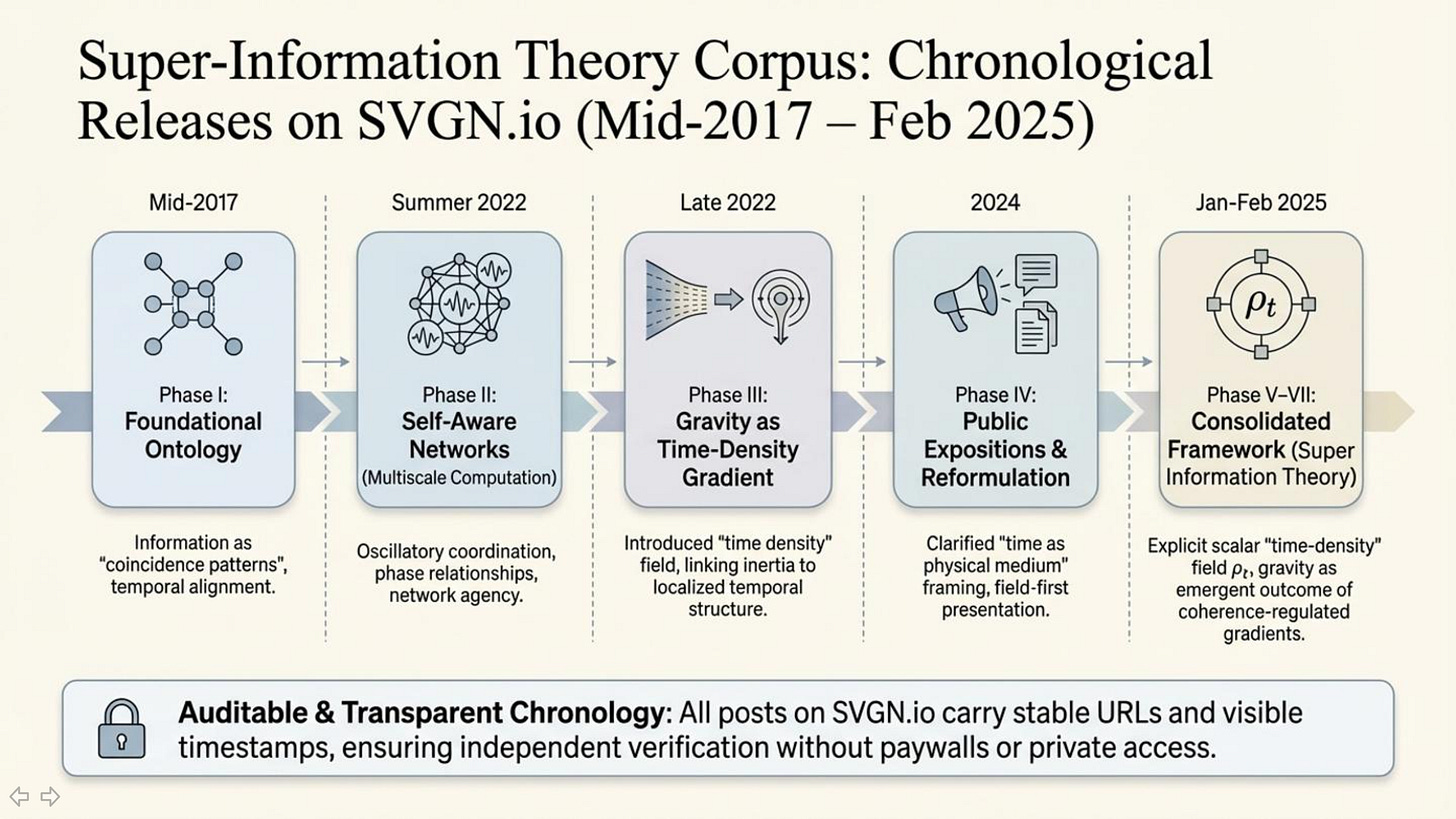

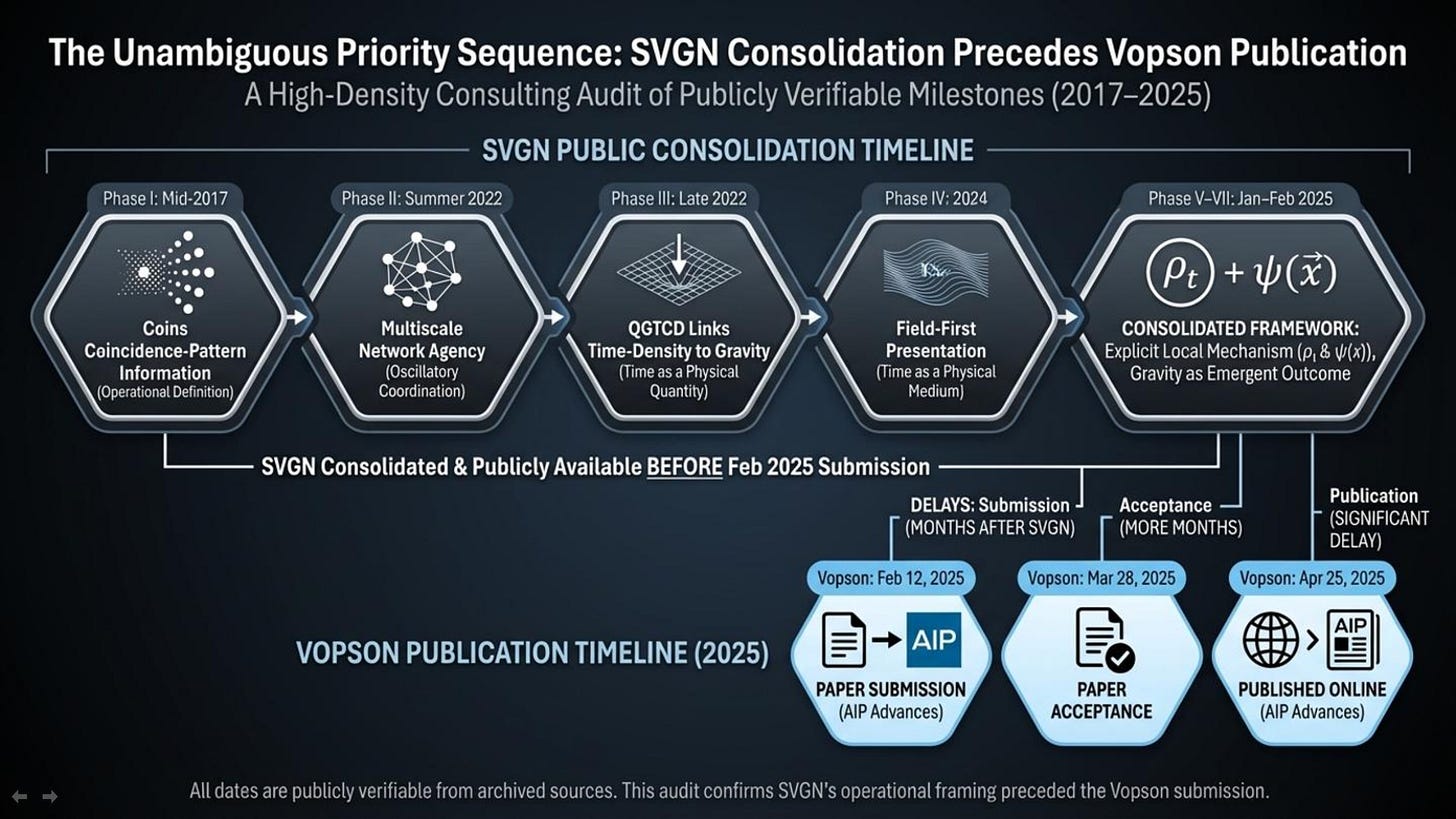

Mid-2017 (Phase I): Public work begins with an operational definition of information as “coincidence patterns” (information treated as temporal alignment/registration rather than static symbols), establishing the foundational information-first ontology that later extensions build on. SVGN

Summer 2022 (Phase II): The framework is extended into a multiscale computational program (Self Aware Networks), emphasizing oscillatory coordination, phase relationships, and network-level agency as the compositional substrate of information. SVGN

Late 2022 (Phase III): The program is explicitly extended into gravity via QGTCD, introducing “time density” as a physical quantity and framing gravity as arising from gradients in a time-density field (linking inertia/gravitational attraction to localized temporal structure). SVGN

2024 (Phase IV): A series of public expositions further reformulate and clarify the “time as a physical medium” framing and prepare a more operational field-first presentation of the same primitives. SVGN

January 2025 (Phase V–VI): The work shifts toward explicit local mechanism and operational field naming; time density is treated as a named scalar field (

ρt) and gravity is described as an emergent outcome of local informational dynamics regulated by variations in time density. SVGNFebruary 2025 (Phase VII): Super Information Theory is consolidated and published as a unified framework built on two informational primitives (coherence field

ψ(x)and time-density fieldρt(x)), with gravity described as emerging from coherence-regulated time-density gradients. SVGNFeb 12, 2025: Vopson’s paper (“Is gravity evidence of a computational universe?”) is submitted to AIP Advances. SVGN

Mar 28, 2025: Vopson’s paper is accepted. SVGN

Apr 25, 2025: Vopson’s paper is published online in AIP Advances. SVGN

Dec 23, 2025: Popular Mechanics publishes its article framing the gravity→information→simulation angle as “groundbreaking new research.”

That sequence is the central factual point: the public record contains earlier, accessible work describing the same high-level framing before the later submission and before the “new breakthrough” media narrative.

Where This Prior Work Lives (and Why It’s Easy to Verify)

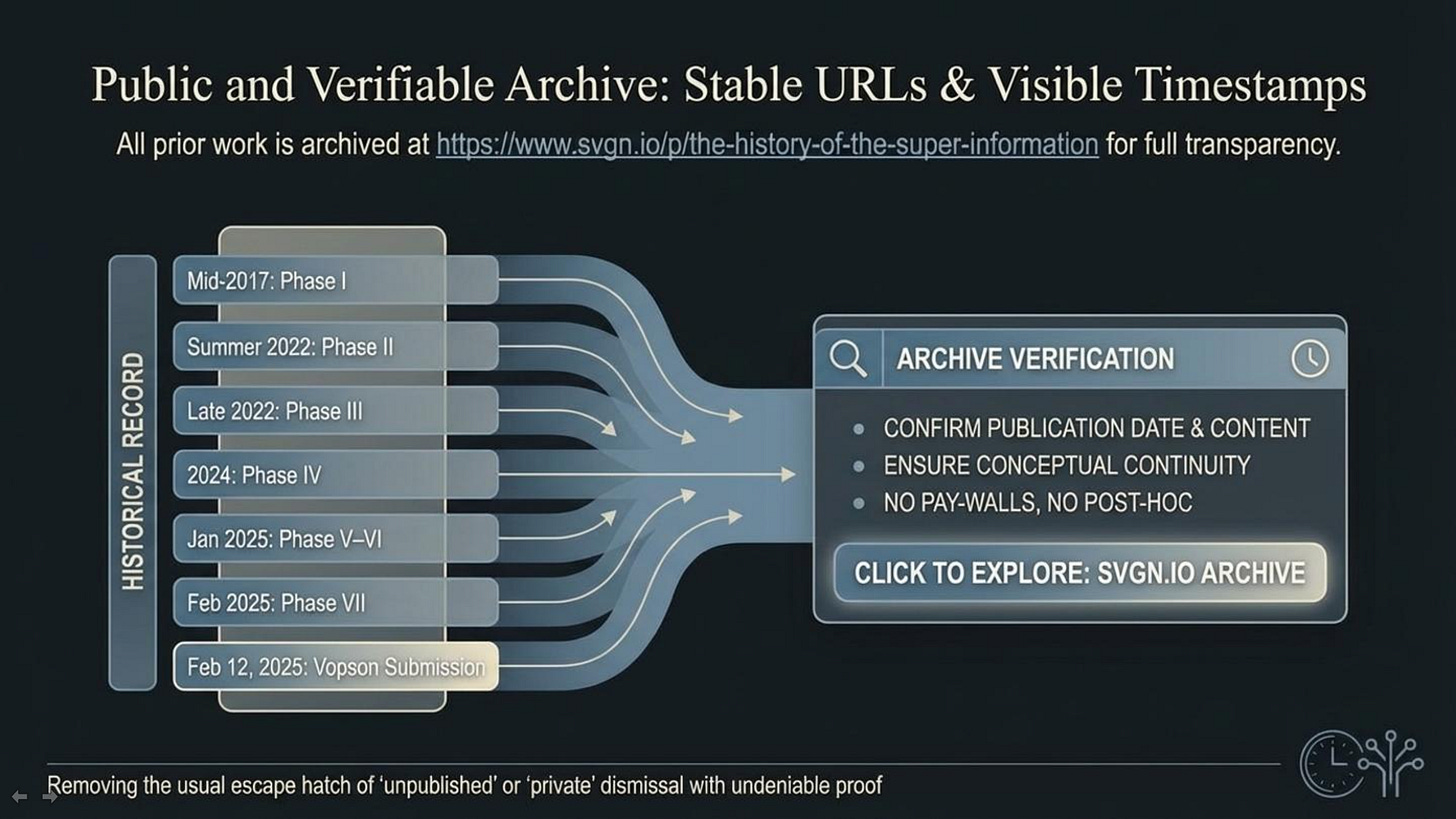

The prior work referenced here is not “private,” not behind an academic paywall, and not dependent on anyone taking my word for it. It is publicly archived on SVGN.io in a way that is designed to be easy for readers to check.

Right above this section, I linked a consolidated historical index that serves as a single verification hub: https://www.svgn.io/p/the-history-of-the-super-information. That page is structured specifically to document the development of the Super Information Theory corpus from its early foundations (2017 onward) through later expansions, and it includes direct links to the relevant public posts and releases along with timestamps. In other words, it is a navigable record of what was published, when it was published, and how the ideas evolved across time.

This matters because the easiest way to dismiss priority claims is to imply the work was “unpublished,” “private,” “not accessible,” or “only described after the fact.” A public archive with stable URLs and visible timestamps eliminates that ambiguity. Readers do not need to agree with the theory to verify the chronology. They only need to click the links, check the dates, and compare what is being claimed as “new” against what was already publicly available.

This Is Not About Ownership — It’s About Attribution

This is not an argument that no one else may work on these ideas. Science advances through convergence: multiple people can arrive at similar framings, refine them, test them, and challenge them from different angles. Nothing about this discussion requires anyone to “pick a side” or treat a concept like private property.

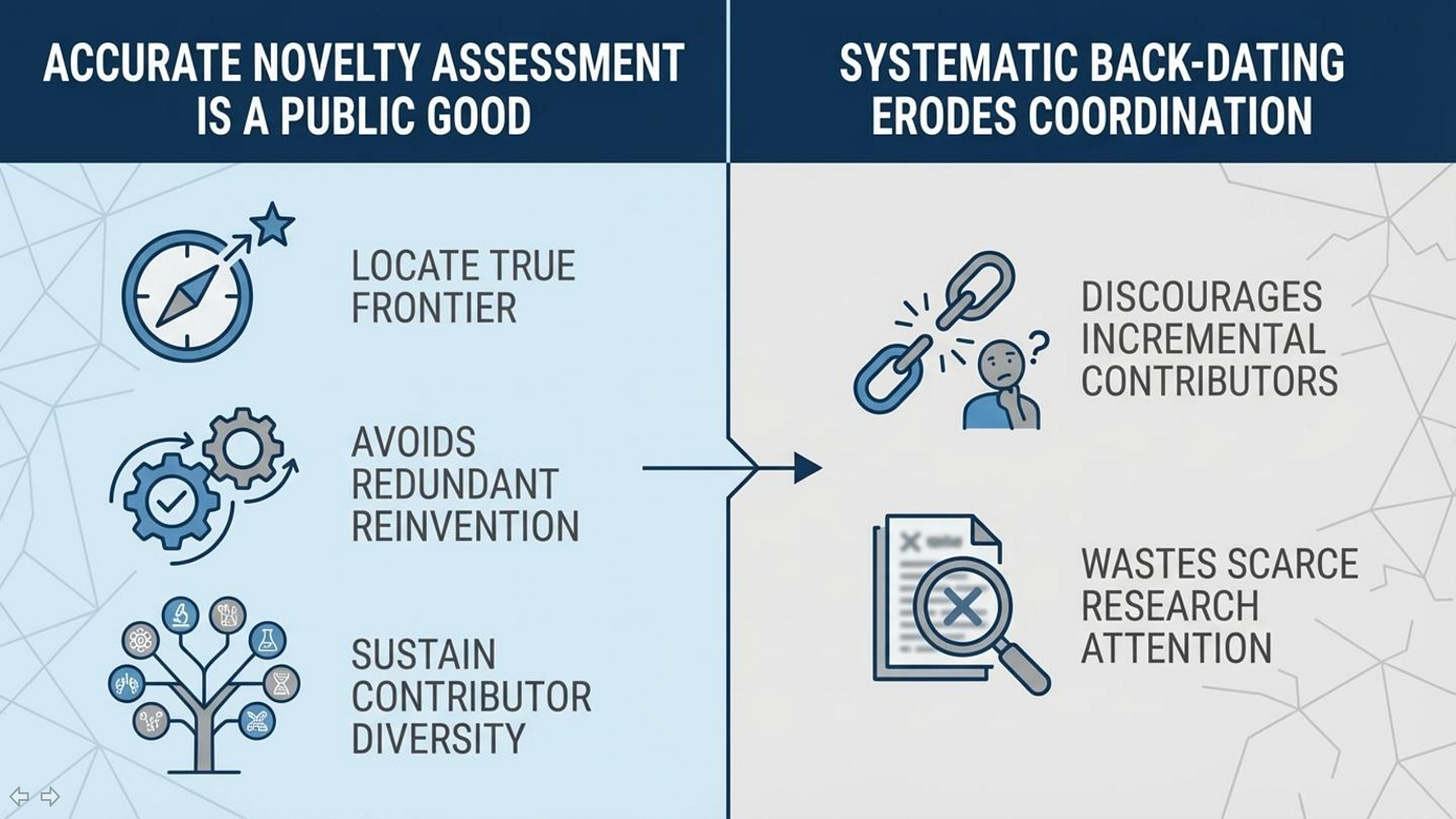

The issue here is narrower and more specific: attribution—and, in particular, the difference between something being newly published versus newly discovered. A paper can be new in the sense that it has just appeared in a journal. But the core conceptual move it presents may not be new in the broader public record. When an outlet frames a concept as a “groundbreaking new idea” without acknowledging earlier public work that already developed the same framing, it gives readers an incomplete—and often misleading—picture of novelty.

So the claim being made in this article is not “I own the idea.” The claim is simply that the public record contains earlier work that matters for context, and that this context was not mentioned when the idea was presented as new.

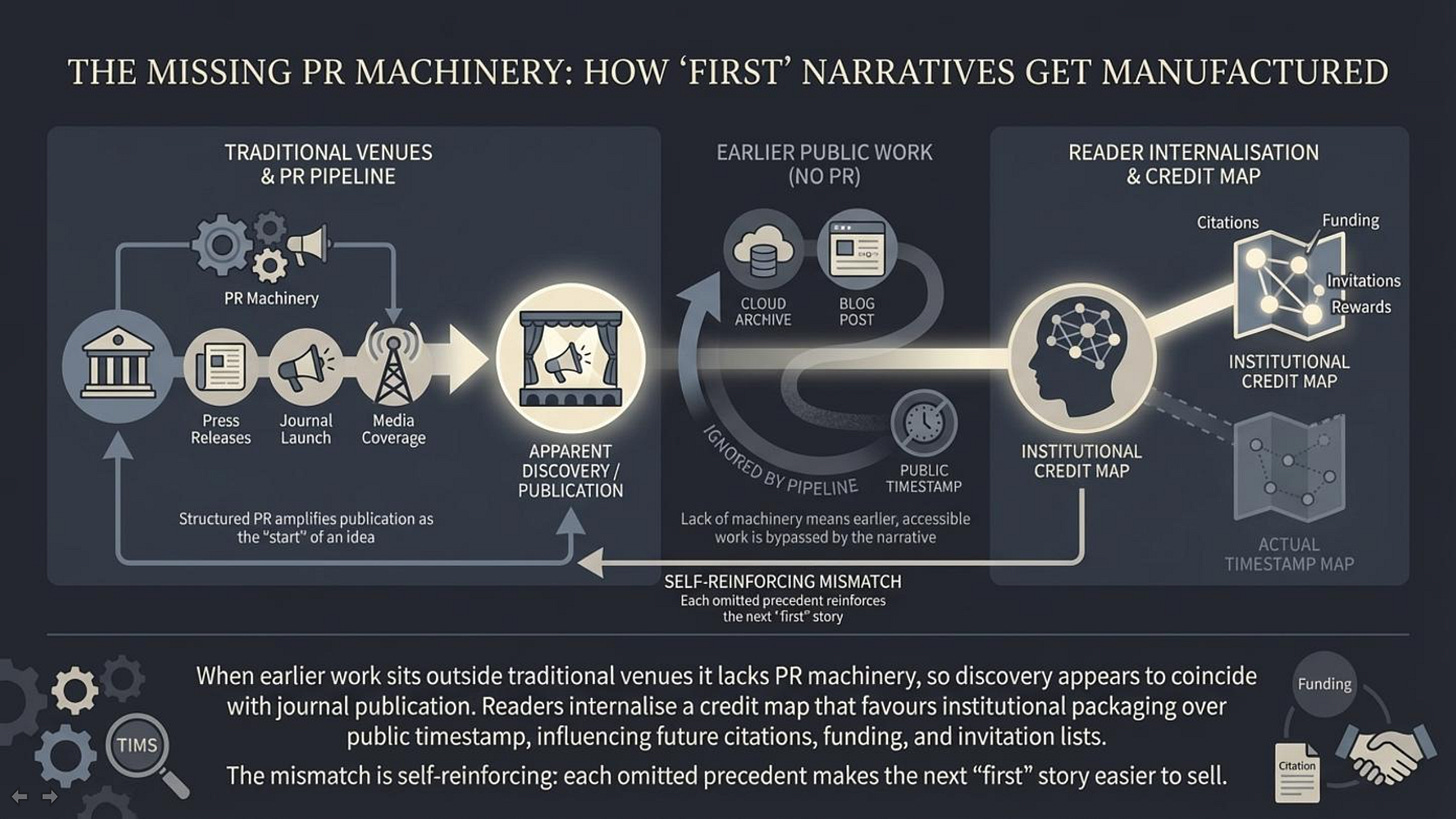

6. How “First” Narratives Get Manufactured in Science Media

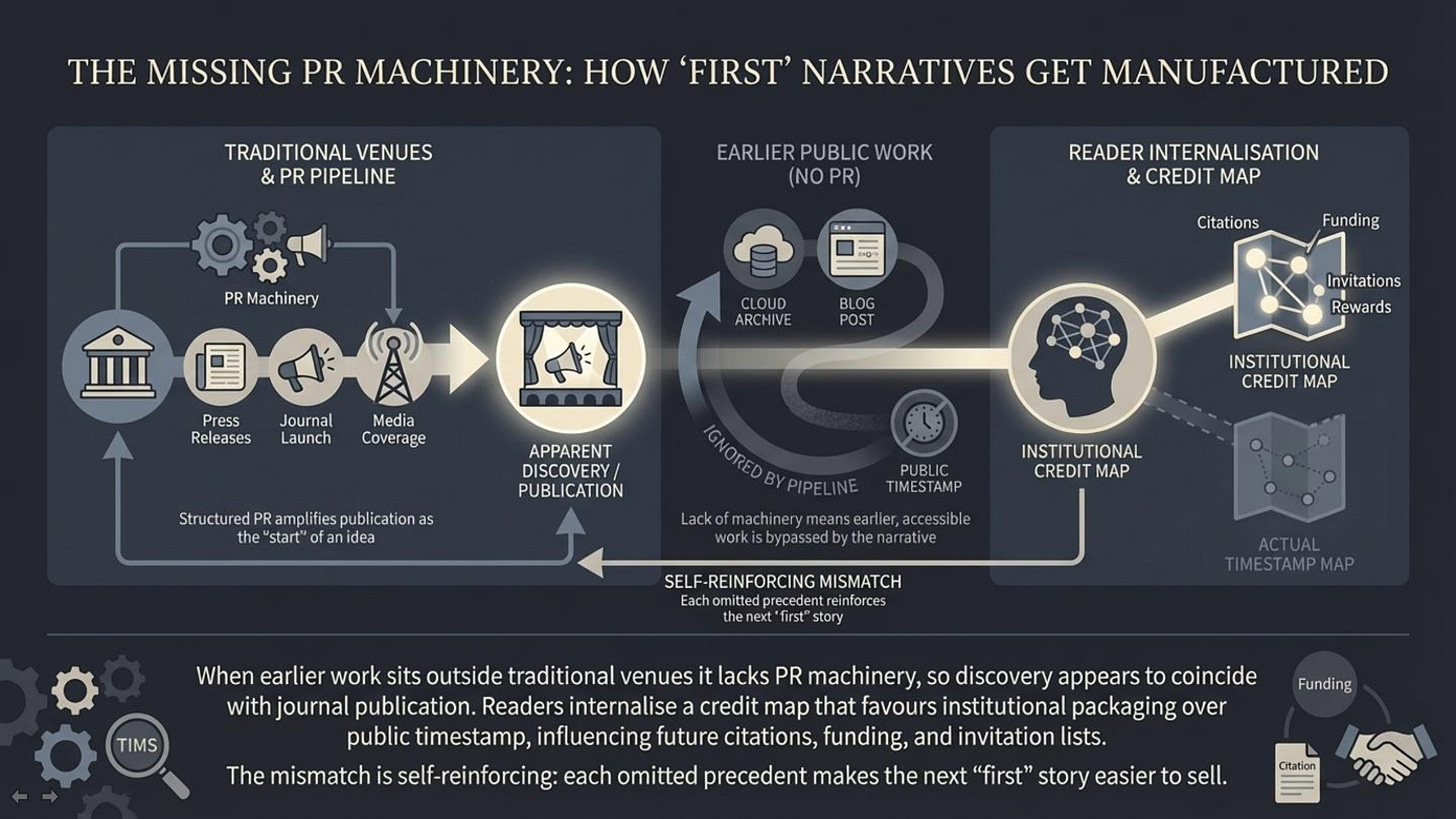

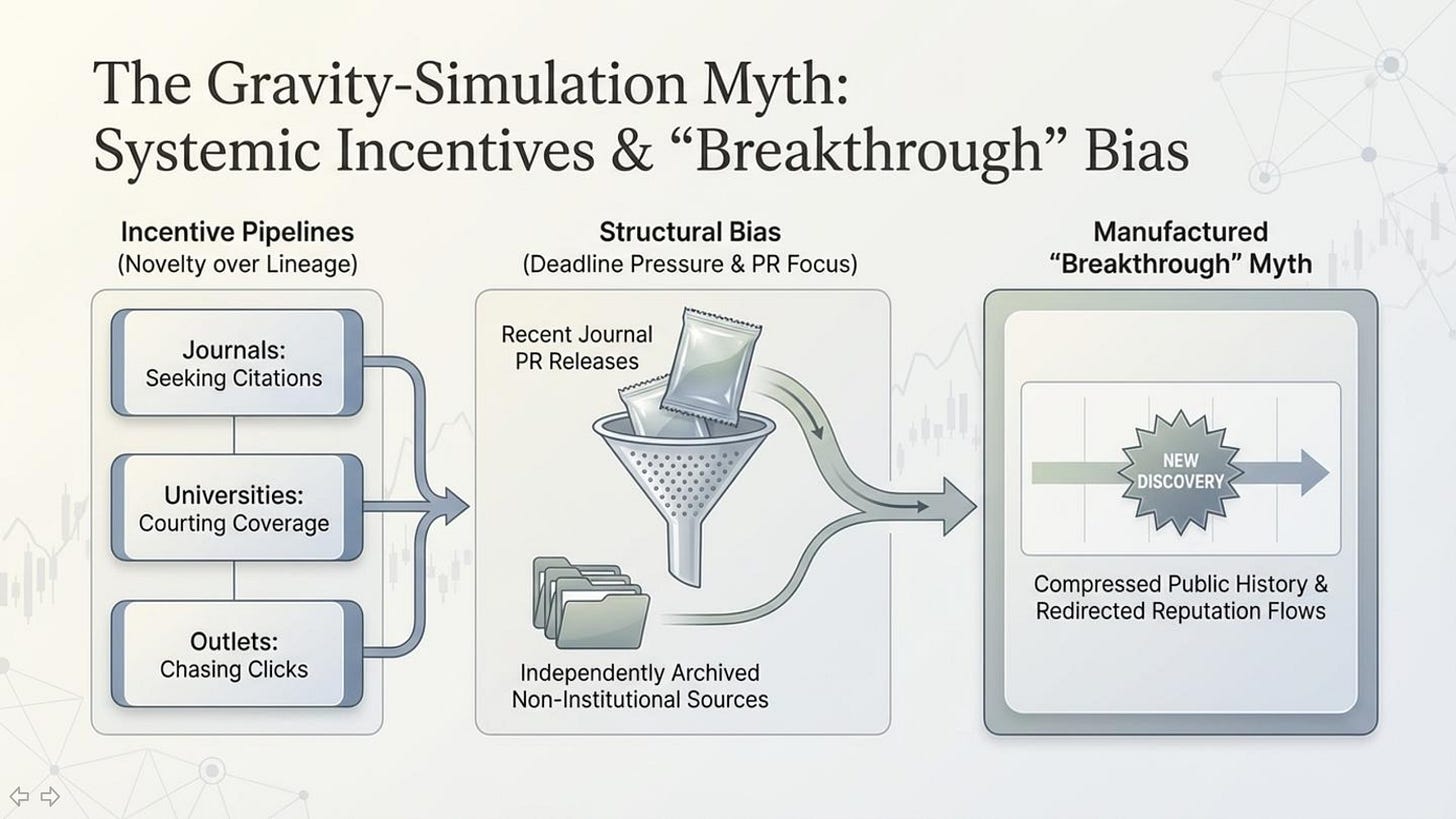

This situation is not unique to any one topic. It reflects a recurring structural problem in science media: novelty is rewarded, and “first” is easier to sell than “latest.” Journal press releases and institutional communications are often written to emphasize what’s exciting and what’s new. Journals want attention, universities want coverage, and outlets want clickable narratives with a clean hook. The result is a pipeline that reliably produces “breakthrough” framing—sometimes even when the underlying idea has a longer history.

None of this requires conspiracy thinking. It’s an incentive system plus a time constraint system. Reporters frequently operate under tight deadlines, with limited space and limited time to perform deep literature archaeology. And the search process is biased toward what is easiest to find: recent journal publications, PR summaries, and sources that appear “official” by virtue of institutional packaging.

That dynamic becomes especially distorting when earlier work exists outside traditional venues—such as independent archives, long-running public research blogs, preprint ecosystems, or serial publications that don’t sit neatly inside a single journal database. Even if the earlier work is publicly available and clearly timestamped, it can be overlooked simply because it wasn’t funneled through the same PR-and-journal discovery pipeline. Readers are then left with a story that feels authoritative while missing key context.

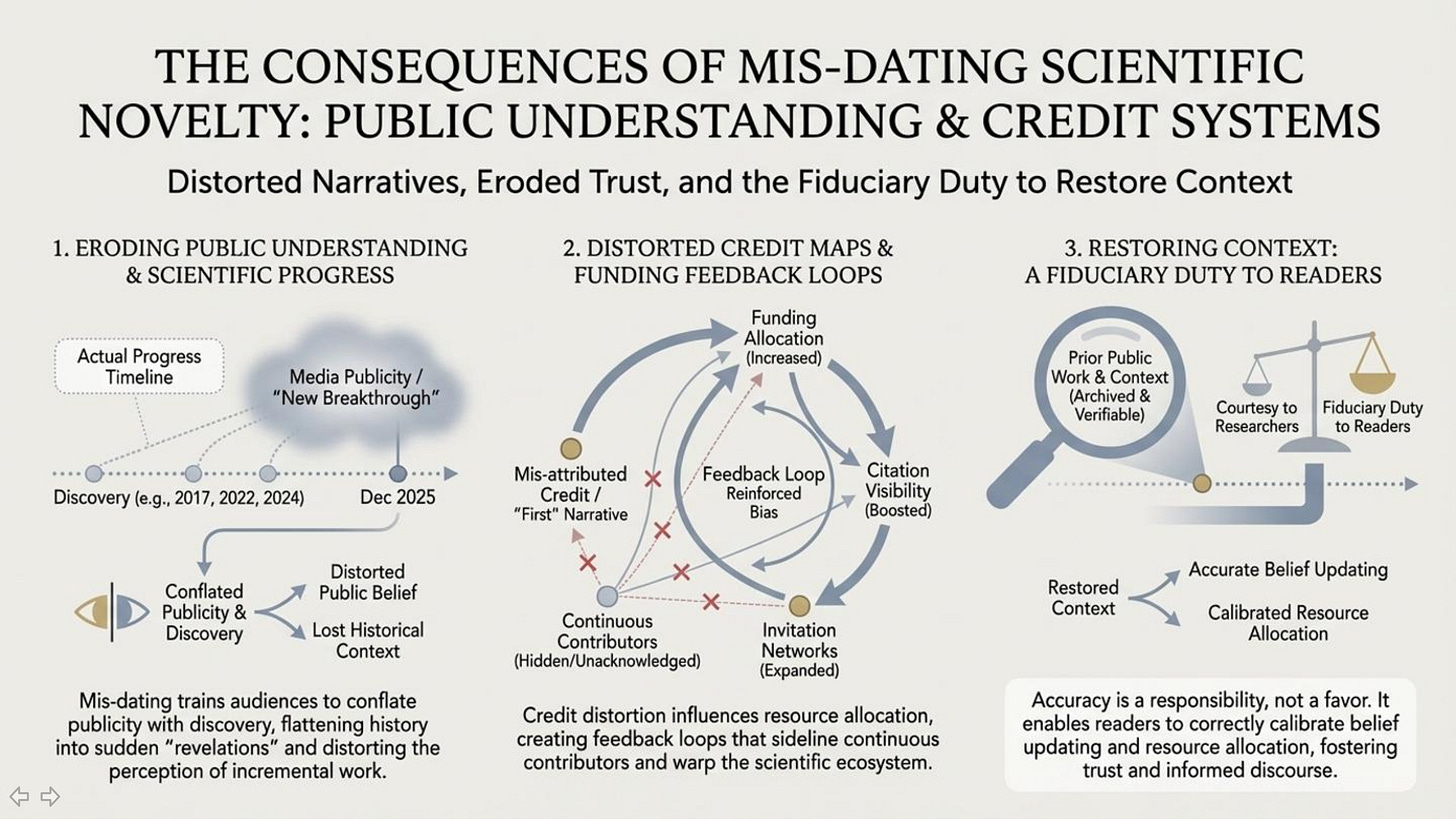

7. Why This Matters to Readers

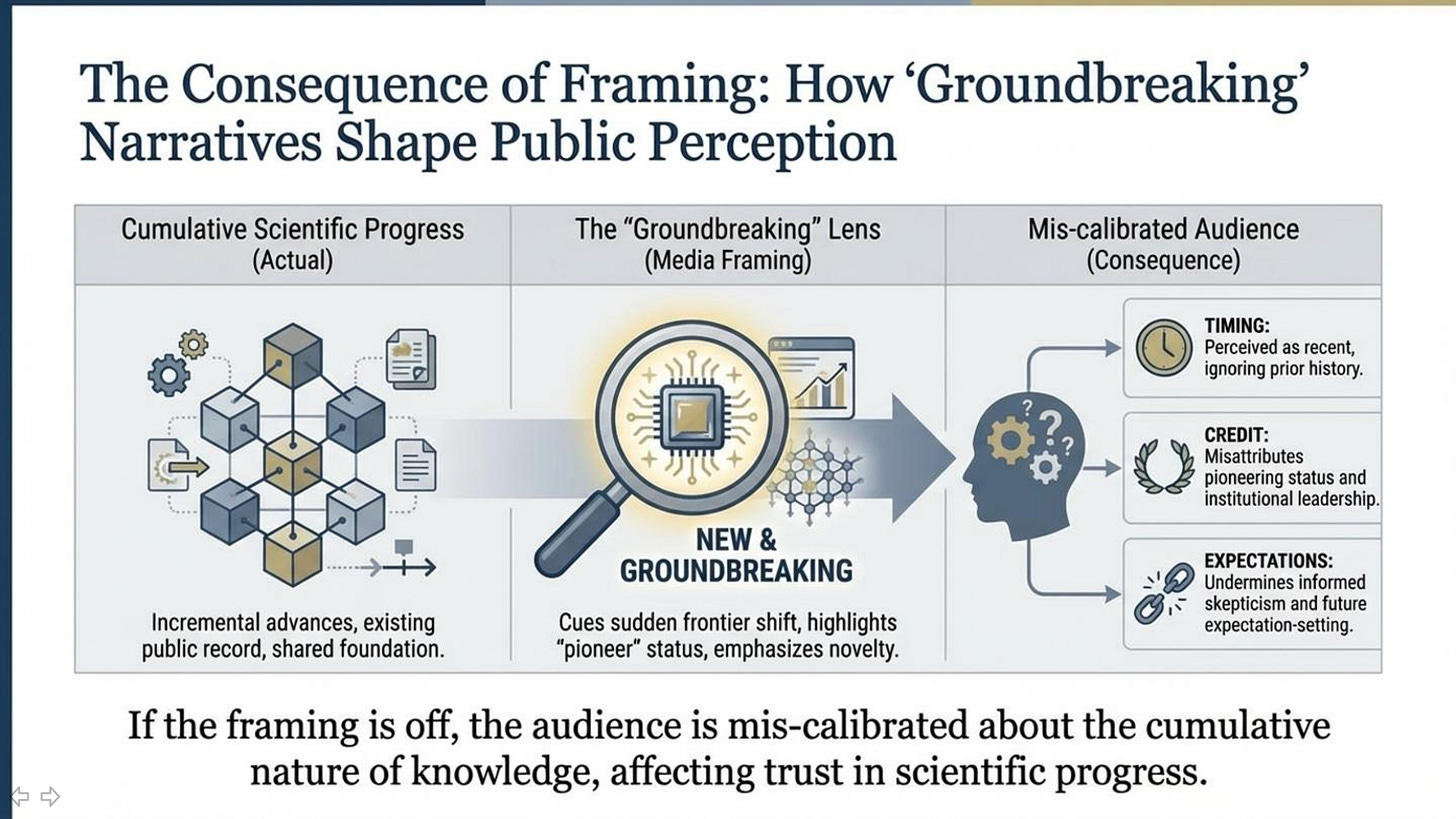

This matters because readers deserve accuracy about how ideas actually develop. When an outlet tells people an idea is new when it isn’t, it doesn’t just flatten history—it reshapes the public understanding of scientific progress into a sequence of sudden “discoveries” rather than a long chain of incremental work, debate, and cross-pollination.

It also affects trust. Science journalism asks readers to accept uncertainty, to update their beliefs, and to follow evidence. That only works when the narrative is careful about what is truly novel and what is part of an existing lineage. If “groundbreaking” becomes shorthand for “recently covered,” readers are trained to confuse publicity with novelty.

Finally, credit matters because it influences who gets heard next. Media attention shapes reputations. Reputations shape invitations, citations, funding interest, and which ideas are treated as legitimate lines of inquiry. When the historical record is compressed into a “first” narrative that omits prior public work, it doesn’t just misinform readers—it actively redirects the map of who is perceived as contributing to the field.

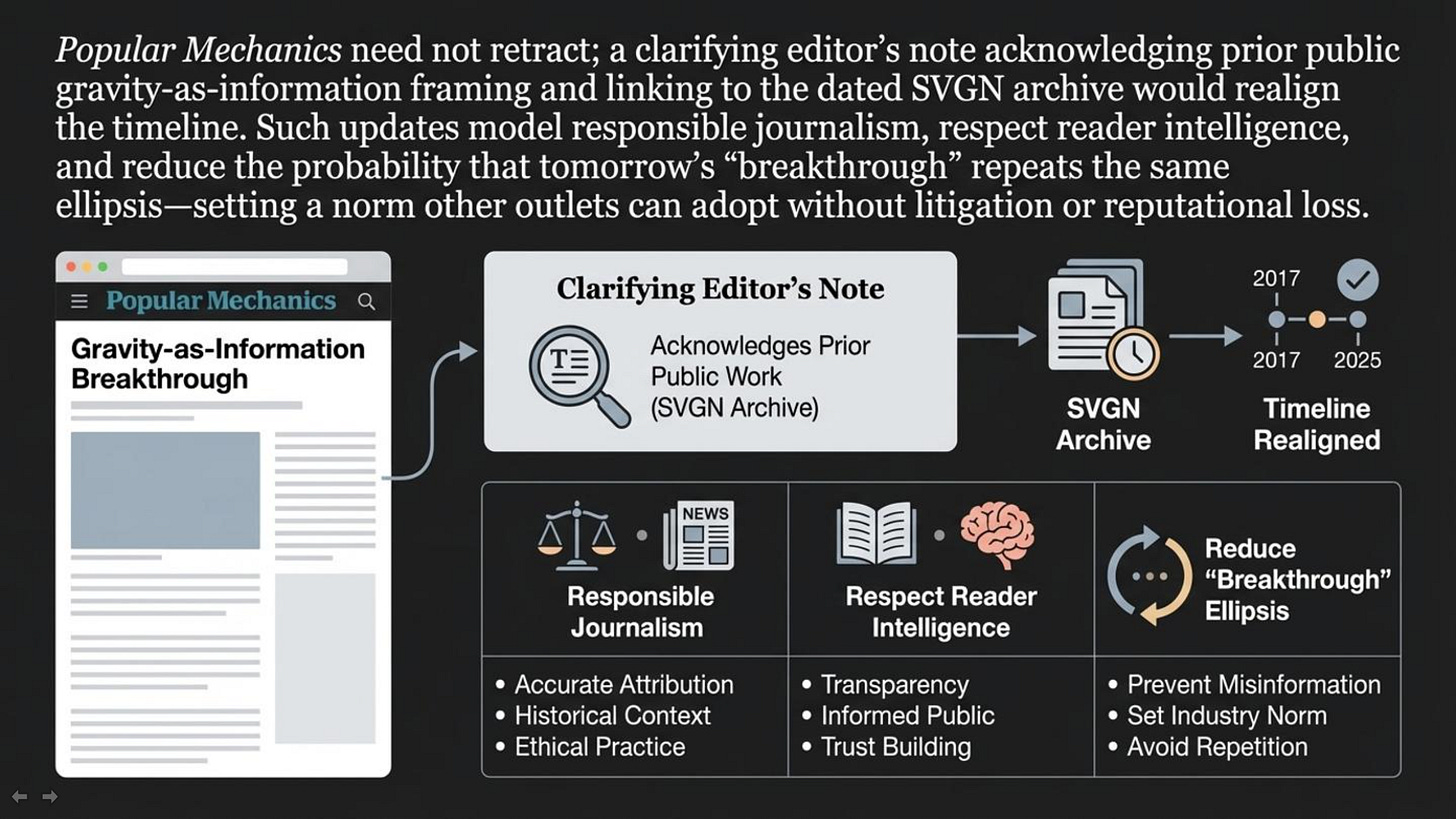

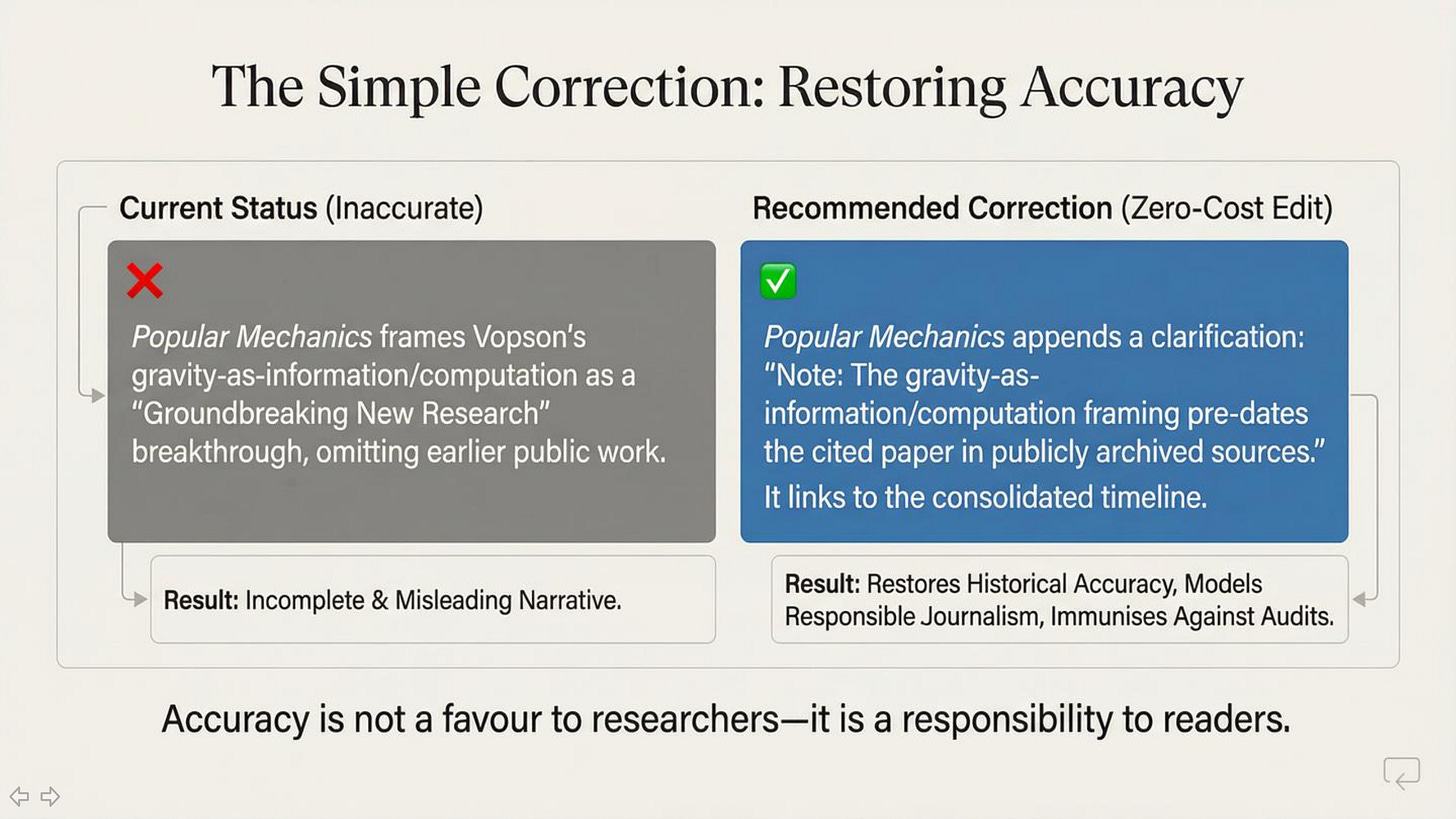

8. A Simple, Fixable Ask

None of this requires a fight, and it does not require a retraction. It requires a small correction that restores context.

A simple, professional fix would be for Popular Mechanics to add a clarification acknowledging that the gravity-as-information/computation framing predates the cited paper in the public record, and to link to that prior work so readers can see the broader timeline for themselves. This is not about endorsing any particular framework. It is about accurately describing the state of the idea: not “newly discovered,” but newly packaged and newly promoted.

That kind of correction would strengthen the article, not weaken it. It would show respect for readers, improve historical accuracy, and reduce the risk of the outlet unintentionally amplifying a misleading “first” narrative.

9. Closing Line

Accuracy isn’t a favor to researchers — it’s a responsibility to readers.